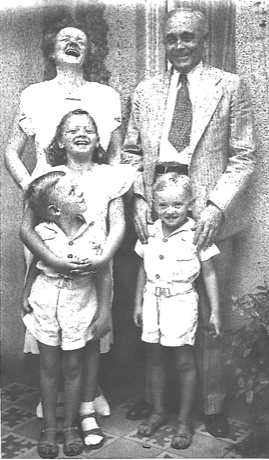

Clockwise from top left: Ravenna W. Mathews, E.J. Mathews, Edward Mathews, Reed Mathews, Ravenna Mathews (Helson) - 1933

One Surprise After Another

Ravenna Mathews Helson never stopped wondering. Hers was a lifetime of exploration, studying lives in multiple contexts and the Jungian theory that gave them meaning. Her boundless enthusiasm for this investigation has been an unending inspiration to those around her.

Early on Ravenna wanted to be a preacher, a writer, or a journalist. Soon, however, she fell in love with the process of discovery and investigation itself, first as a reporter, then as wife, mother and psychologist.

She earned Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees at the University of Texas at Austin and then received a PhD at the University of California, Berkeley in 1949. While teaching subsequently at Smith College she met mathematician Henry Helson, and, after marrying, they moved to Berkeley where he had been offered a position at the University of California. She was overjoyed not long after to receive an unexpected invitation to join the Institute of Personality Assessment and Research (IPAR) where in 1955 Don MacKinnon was directing a small, dynamic and academically diverse group of psychologists consisting of Robert Harris, Erik Erikson, Nevitt Sanford, Richard Crutchfield, Harrison Gough, Frank Barron and Ronald Taft, with Wallace Hall as archivist. IPAR was heavily influenced by Henry Murray’s Personological tradition which studied the whole person, focusing on people and their motives rather than particular traits and included the study of myth and literature. This approach involved gathering a lot of information in a variety of ways that combined ‘tough and tender’ methods. The highly effective person was the focus of investigation with originality as a key feature. Studying positive functioning was an important change from the usual emphasis on the abnormal. Creativity was a new frontier and IPAR was busy developing new methods and techniques for studying it, including the CPI and the ACL.

For several decades Ravenna was the only woman on this team. She said that for years her highest ambition was to be worthy of the institution. It felt like the court of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table in search of their holy grail - understanding the unconscious and how it manifests in personality. Don McKinnon was the King Arthur who brought together ambitious knights, pursuing diverse quests while uniting around the common goal of doing justice to the complexity of personality and psychological functioning.

Motherhood came quickly after arriving in Berkeley, making Ravenna’s mid-30’s a peak time of change, pain, joy, and richness that she says shaped the rest of her life, putting family ‘at the marrow of her existence.’

One morning in 1955 MacKinnon asked her to take over IPAR’s proposed project on creativity in women. “What a surprising and great assignment!” Merlin was indeed at work! She began her studies of creativity in women—mathematicians, authors of fantasy for children, and the Mills College graduates of 1958 and 1960. Still, with a half-time appointment, babies at home and intermittent semesters abroad for Henry’s sabbaticals, publications were slow to come. She felt lonely in her avant-garde feminist consciousness. “I felt that I was the only one who really cared whether Ravenna the psychologist survived.” She was devastated when the reviewer of her first monograph on creativity in the Mills study said, “sample was too small but 1,000 creative college women would not be worth a whole monograph!”

Ravenna persisted. In 1970, she suggested teaching the first women’s studies class at UC Berkeley - Personality, Sex, and Society. It would eventually be offered off-campus in a church basement through the Extension Program. “It was exciting to find materials and work it up,” she recalled. There she met Valory Mitchell (who, many collaborations later, would co-author their book chronicling fifty years of studying those Mills women, Women on the River of Life; a Fifty-Year Study of Adult Development).

In 1980, Merlin was again making magic, and the Mills study became a lifelong project for Ravenna. With funding to transition it into a longitudinal study of women’s adult development, she had come into her full stature as an academic. “I had a persona, a grown-up dress to wear!” She had a research team, grant proposals to envision, fund and fulfill, students to work with, opportunities to be generative!

Wonderful colleagues spent sabbaticals or worked with Ravenna at IPAR, now the Institute of Personality and Social Research (IPSR). Studying the lives of the Mills women over fifty years was the work of many and the richness of collaboration was ‘magical.’ Her personality, life, times and work were interwoven with theirs, and she felt privileged to call them friends. They studied old topics such as sex roles and creativity in a new longitudinal context while finding new ones such as emotion, wisdom, attachment, and personality change distinctive to women. She was excited to discover paths and patterns in women’s lives, links between women’s family lives, work lives, and individual personality differences. Along the way, she received awards including the Sir Francis Galton Award for outstanding contributions to the study of creativity (2000) from the International Association of Empirical Aesthetics, the Henry A Murray Award (1984), the Block Award (2002) and the 2017 Legacy Award for Lifetime Achievement from the Society for Personality and Social Psychology. In 2021 she received the Florence Denmark Award for Contributions to Women and Aging, from APA Division 35 (Psychology of Women).

In Milwaukee, the nature of Ravenna’s creative work was not academic but relational. She said she wished she had arrived at eighty with a little less “lead” in her personality and now she realized that the years of toughness required to survive academic life were unnecessary to carry forward. She came alive in a new way. In the company of her new collaborators, others in their 80’s and 90’s in the Saint John’s community, she learned and shared much that was previously unexpected and unknowable. At ninety, after many years of attending Quaker meeting, she committed to membership in the Milwaukee Monthly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends.

Ravenna, a “pioneer in the study of women’s lives” and creative and productive to the end, passed on October 2, 2020, at the age of 95, just days after seeing her remarkable life’s work in print.